History of Research & Archaeological Sites

100 years of research

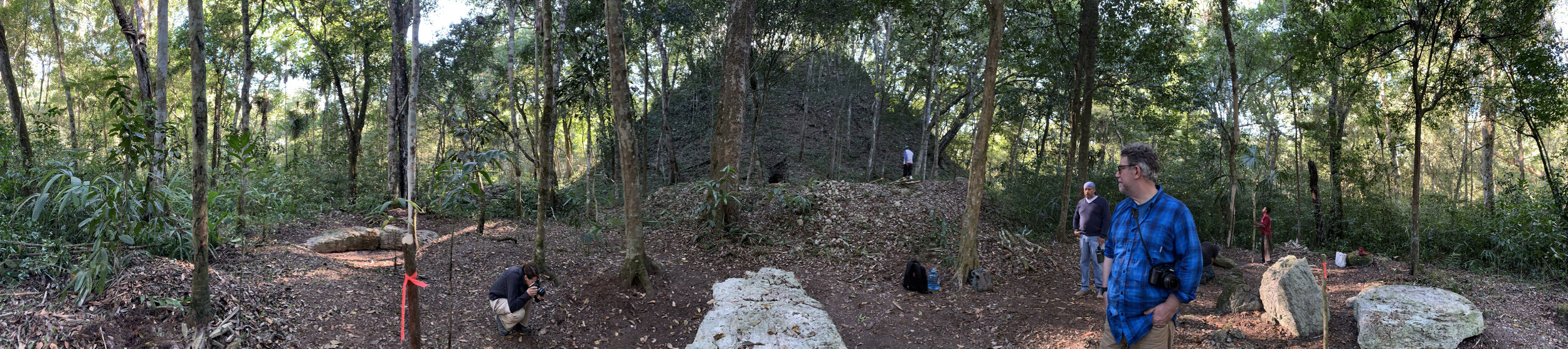

1920 - 2000

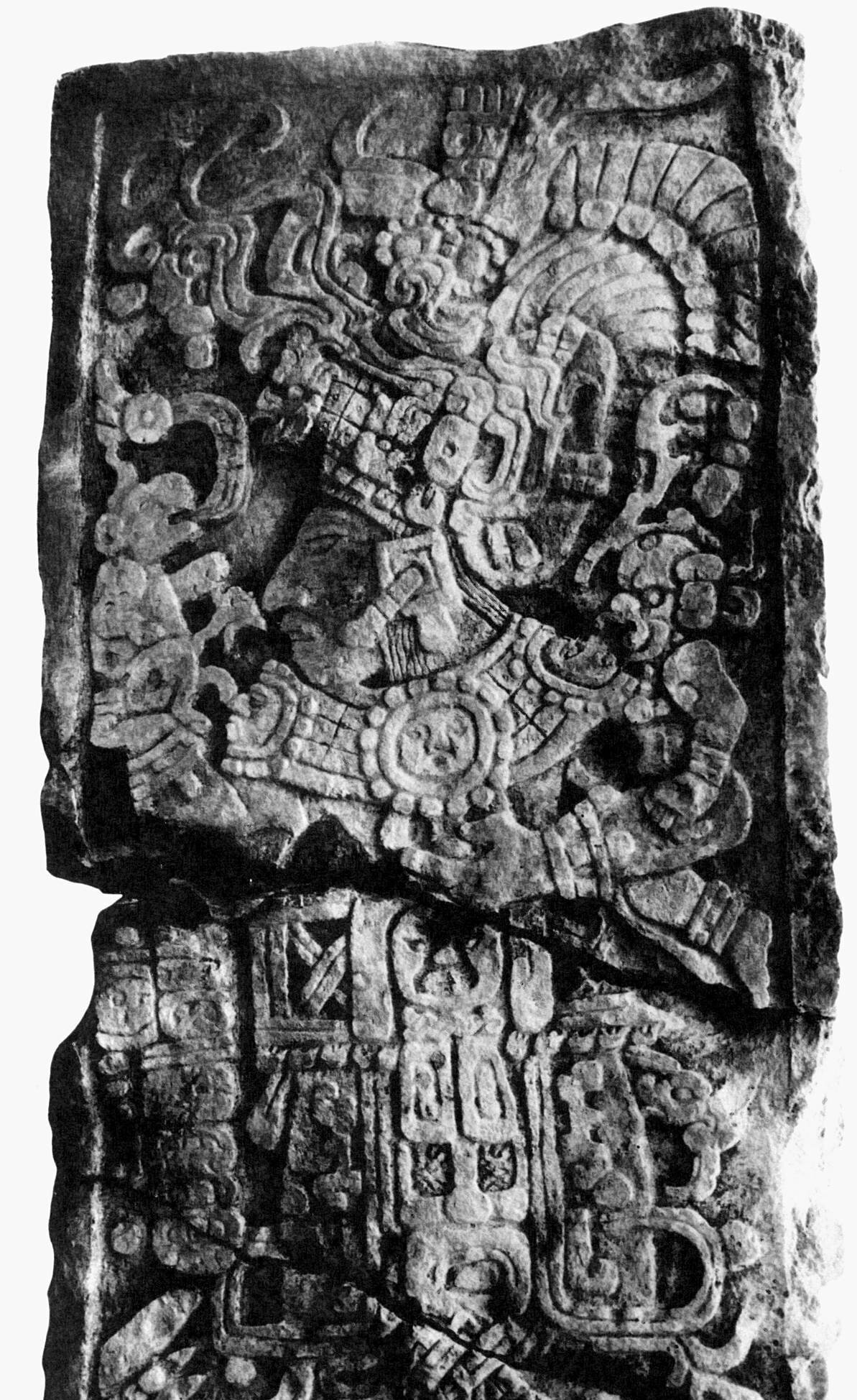

Sylvanus Morley was told about a large ruin by a chiclero (gum-resin harvester) named Aurelio Aguayo, who claimed to have first come across the jungle city five years prior. He was not disappointed, excitedly calling the site “the largest city of the Old Empire in northeastern Petén.” It was during this first visit that Morley and his team named the site Xultun—xul meaning “end” and tun meaning “stone” in Yukatek Mayan. This name was chosen for the 10.3.0.0.0 date of Stela 10 (889 CE), the latest known Long Count date in the Maya Lowlands at the time. Between 1921 and 1924, the Carnegie Institution generated a rough map of Xultun’s main architectural groups and documented its carved monuments.

In the 1970s in the midst of the Guatemalan Civil War, Erik Von Euw spent several months at Xultun on behalf of the Harvard Corpus of Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Project. He noted the disappearance of various monuments including Stela 10 and widespread looting was underway, the scars of which are still visible across the site. The site would remain known only through its monuments for approximately 90 years until the first archaeological excavations by PRASBX.

Photo of Xultun, Stela 10 by S. Morley, courtesy of the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Project, Harvard University.

2001 - 2021

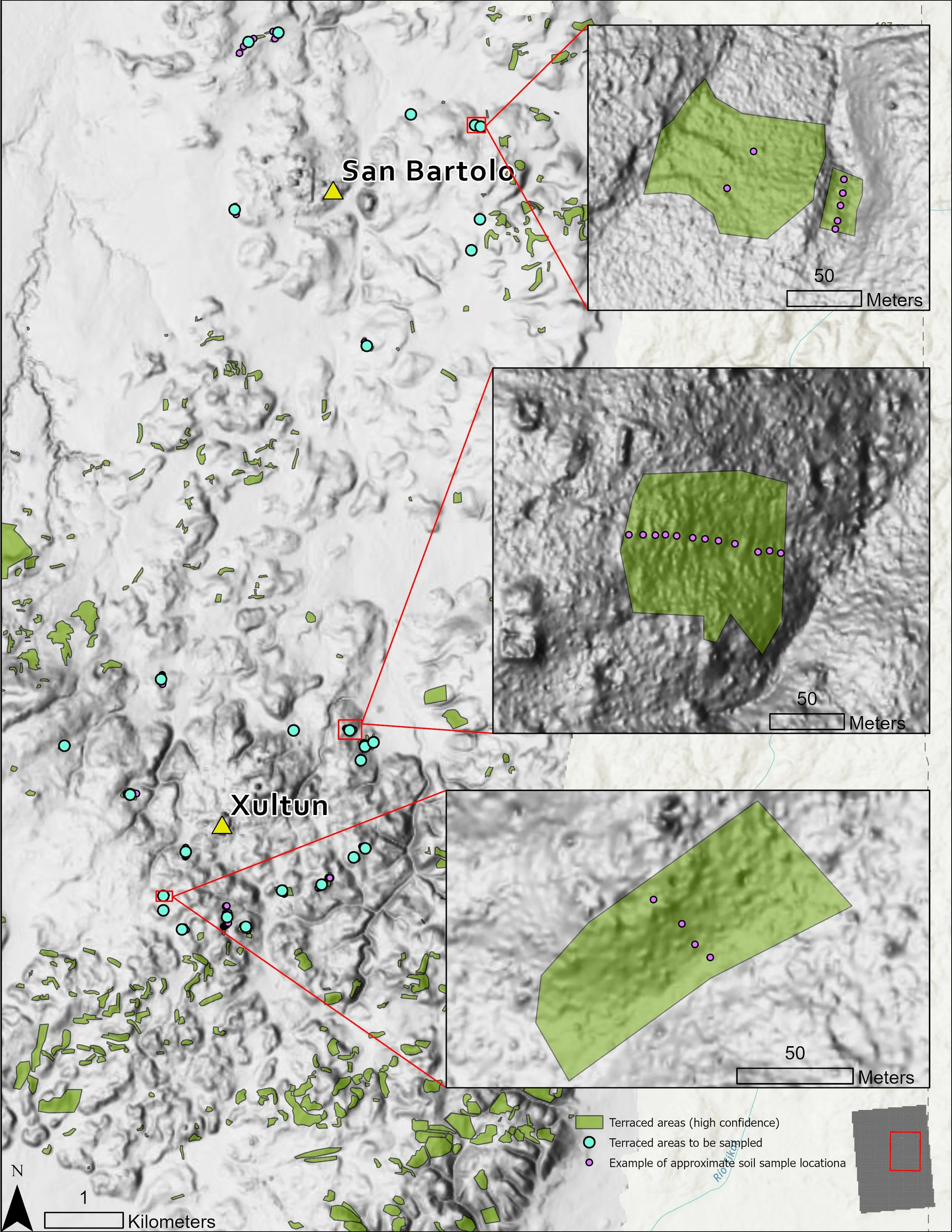

Just nine kilometers to the north of Xultun is the smaller site of San Bartolo. Unlike Xultun, this site was undocumented until 2001, when San Bartolo was first registered by William Saturno during reconnaissance for the Harvard Peabody Museum’s Corpus Project (following in Morley’s footsteps!). Immediately recognizing the significance of the site’s early in situ mural that had been partially exposed by looters, Saturno assembled a research team who collaborated to excavate, document, and conserve the mural and its many fragments. With the murals as its catalyst, the SBX project began in 2001 and concurrently investigated site occupation and questions of material culture, political complexity, regional urbanization, and human-landscape interaction at San Bartolo. The project expanded its study to Xultun with a research program beginning in 2010, after a season of mapping and test-pitting. Xultun is a very large city with a dense core of public buildings, large plazas, and numerous monuments, surrounded by extensive residential areas. Investigations have focused on settlement distribution, economics and resource use, and local dynastic history, as well as examining early construction phases through tunnel excavations. Roughly 20 years after San Bartolo was first mapped by archaeologists, lidar has revolutionized topographic visualization and sparked a new wave of research at SBX.

San Bartolo, Sub-1A chamber, north wall, detail of the Maize God Queen (ca. 100BCE), photo by H. Hurst.

PRASBX’s interdisciplinary approach:

San Bartolo - Xultun Archaeological Overview

Late Preclassic period

San Bartolo is a Late Preclassic period community. Although evidence of occupation and farming are documented earlier, all civic-ceremonial complexes follow a similar pattern with their earliest construction phases dating to between 400-200 cal BCE, with the central acropolis of Las Ventanas and the Tigrillo palace founded in the 5th century BCE. In addition to the wall paintings of the Las Pinturas complex, religious beliefs and political structure during this period are understood through ritual deposits, including this small sculpture and ceramic vessel (left) depicting two deities associated with rain (top) and creation (bottom), as well as architectural trends, household material culture, and subsistence practices.

San Bartolo artifacts

Artifacts from Jabalí complex, excavated by M. Pellecer, photo PRASBX, now in Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala City.

How do we know?

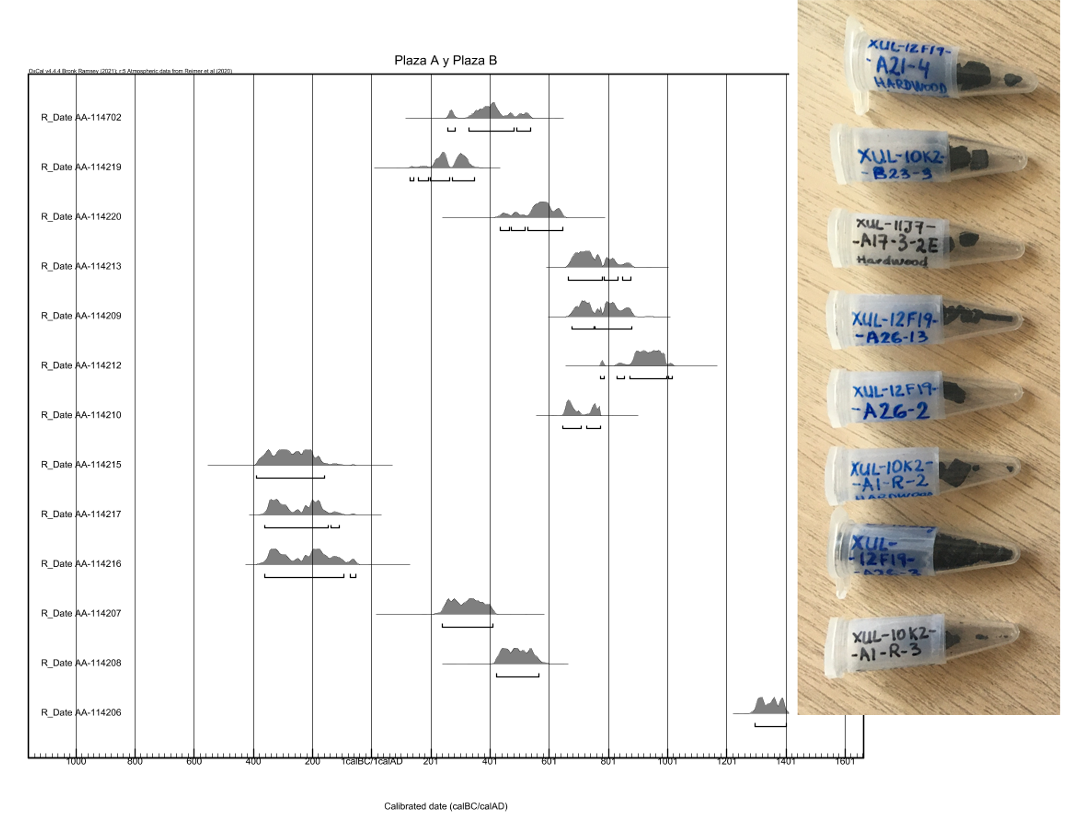

Radiocarbon dates complement robust archaeological, architectural, epigraphic, and ceramic analysis. We use all lines of evidence to understand the intertwined histories of San Bartolo and Xultun. Although radiocarbon precision may be a window of 100 years and ceramic stylistic analysis broadly identifies the period of production, texts can provide a specific day, month, and year of recorded events. Combining these data enables archaeologists to reconstruct the histories of community residents across thousands of years of occupation.

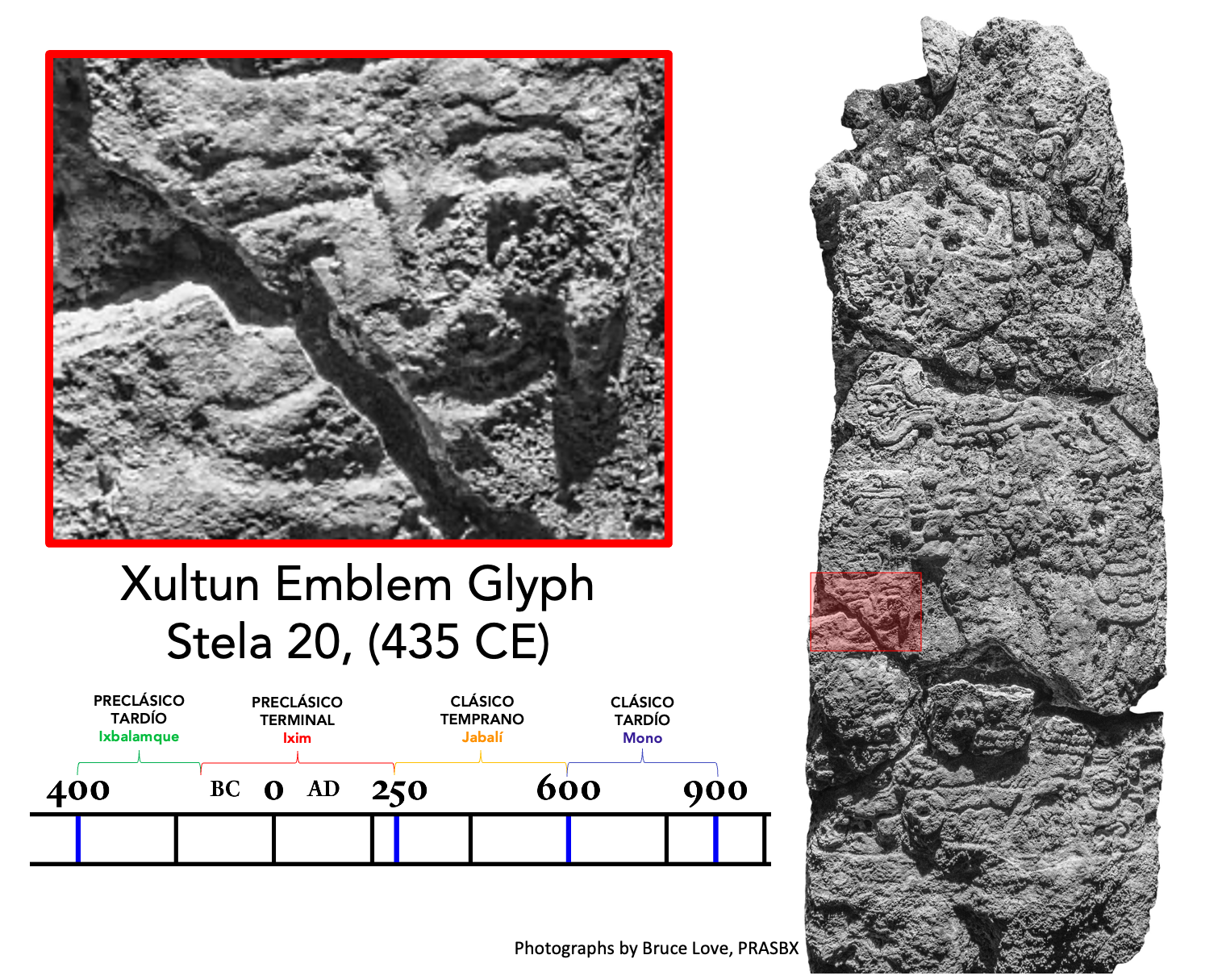

Early Classic period

After a period of social upheaval and large-scale movement of population from 150 to 300 CE, the Maya lowlands enter a period of growth and power consolidation. During the Early Classic period, Xultun exhibits a rapidly growing population and urban expansion with a new focus on dynastic rulership expressed through the practice of inscribing rulers’ portraits on stone monuments (stela). Xultun’s kings and queens were active in the regional geopolitical rivalry among at key centers including Tikal, Uaxactun, La Honradez, and Río Azul. Material culture reflects a growing elite class and courtly traditions.

Xultun stela & artifacts

Early Classic period Stela 20 located in Plaza B with Xultun’s emblem glyph Baax Witz’ Ajaw, or “chert / hammer-stone mountain,” ceramic vessels from Xultun Burial 10, and detail of 4th-5th century sculpted frieze from Xultun’s 12F19 complex, photos PRASBX.

Late Classic period

The 7th to 9th centuries were a dynamic period of alliance building, military campaigns, and changing political fortunes among the dynastic centers in central and northeast Petén. At Xultun, kings erect numerous monuments with increasing frequency and the funerary temples, palace, and elite neighborhoods have evidence of major construction, as well as in extensive agricultural zones. The king Yax We’nel Chan K’inich is depicted in this mural from Structure 10K2 commemorating a New Year’s ritual in 749 CE. Xultun’s kings persist in carving monuments until 889 CE, even as many other dynasties fall in the 9th century. After the royal elite are no longer ruling the site, ritual offerings continue to take place in the now abandoned monumental centers of San Bartolo and Xultun into the 12th – 13th centuries.

Xultun mural “Los Sabios”

Xultun, Structure 10K2, north wall mural detail depicting a mid-8th century king, Yax We’nel Chan K’inich, photo by PRASBX.

Selected sources for further reading

Garrison, T. and N. Dunning. 2009. Settlement, Environment, and Politics in the San Bartolo-Xultun Territory, El Peten, Guatemala. Latin American Antiquity 20(4):525-552. DOI: 10.1017/S1045663500002868 | Houston, S. D. y D. Stuart. 1996. Of Gods, Glyphs, and Kings: Divinity and Rulership among the Classic Maya. Antiquity 70(268):289-312. | Inomata, T., D. Triadan, J. MacLellan, M. Burnham, K. Aoyama, J. M. Palomo, H. Yonenobu, F. Pinzón, and H. Nasu. 2017. High-Precision Radiocarbon Dating of Political Collapse and Dynastic Origins at the Maya Site of Ceibal, Guatemala. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(7):1293-1298. | Saturno, W., D. Stuart y B. Beltrán. 2006. Early Maya Writing at San Bartolo, Guatemala. Science 311: 1281-1283. DOI: 10.1126/science.1121745 | Saturno, W., F. Rossi, D. Stuart, y H. Hurst. 2017. A Maya Curia Regis: Evidence for a Hierarchical Specialist Order at Xultun, Guatemala. Ancient Mesoamerica 28(2): 423-440. DOI: 10.1017/S0956536116000432 | Stuart, D., H. Hurst, B. Beltrán, W. Saturno. 2022. An Early Maya Calendar Record from San Bartolo, Guatemala. Science Advances 8(15): DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abl9290

Our partners

The PRASBX archaeological and conservation program is conducted with the permission of the Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes de Guatemala, through the Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural. We extend our appreciation to the personnel in the office of the Viceministerio del Patrimonio Cultural, the Departamento de Monumentos Prehispánicos y Coloniales, Ceramoteca, Supervisores del IDAEH, and the Inspectoría Regional de Flores, Petén. Our current research activities (2021-2025) are funded by grants from National Endowment for the Humanities, National Geographic Society, Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development of the Netherlands, and the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections, and the generosity of Peter Swift & Diana McCargo and several anonymous individuals. We are deeply appreciative of the institutional support of Skidmore College, the University of Texas at Austin, The Mesoamerica Center & The Casa Herrera, the University of Alabama in Huntsville, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and partnering with the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala and the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala City. Lidar data is provided courtesy of the Pacunam Lidar Initiative. We are grateful for support of our community initiatives for pandemic relief from numerous donors and the Maya Relief Foundation.

Previous support for research at San Bartolo-Xultun includes project awards from: Archaeological Institute of America; Boston University; Boundary End Archaeological Research Center; Brigham Young University; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections; Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies; John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation; National Aeronautics and Space Administration; National Endowment for the Humanities; National Geographic Society; National Science Foundation; Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University; Petén Archaeological Conservation Associates; Reinhart Family Foundation; Rust Family Foundation; Skidmore College; Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute; United States Department of State, Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation; Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala; Universidad del Valle de Guatemala; University of Texas at Austin and the Mesoamerica Center & La Casa Herrera, as well as awards to individual investigators.